By Jennifer Braddock – Editor

In first-person storytelling, dialogue is never neutral. It’s a recounting of memories and is shaped by the narrator’s memory and interpretation of the exchange. For example:

“We’ll see your Papa soon,” Mama said, not looking up from her knitting.

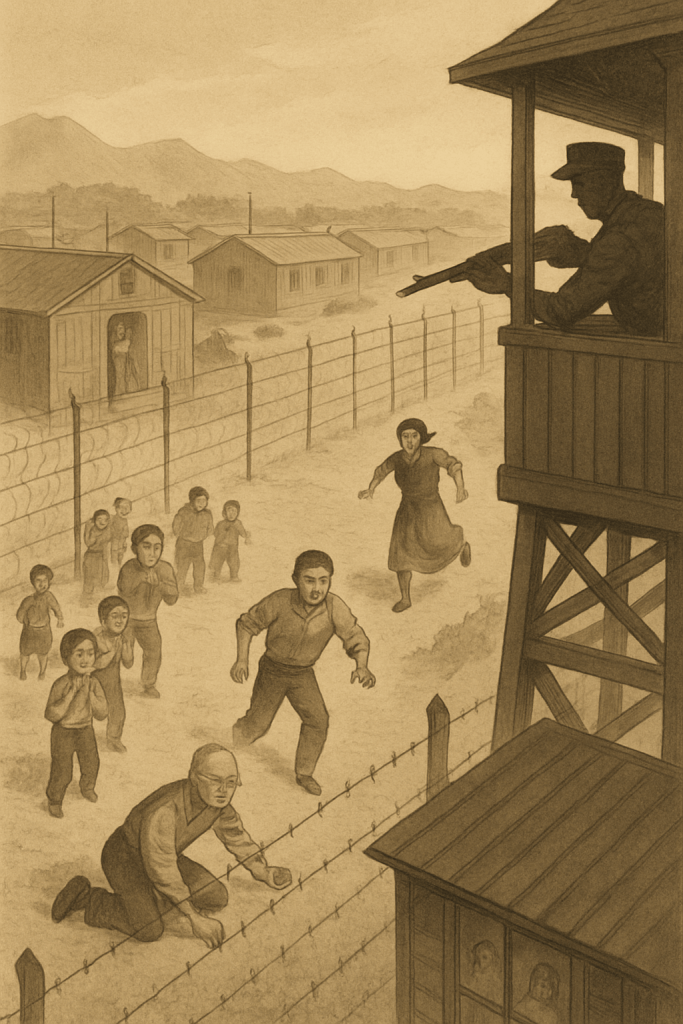

She always had that unemotional tone when she was nervous. I was just a kid when he was arrested by the FBI. I didn’t know what was happening.

Dialogue becomes an opportunity to show character, subtext, and tension, not just deliver facts.

Use these techniques to strengthen first-person dialogue:

- Narrator’s observations: “You’re going like that?” she asked. I looked down at my shirt. Plain gray. A coffee stain near the hem.

- Internal thoughts between lines: “No reason,” she said. Her smile didn’t match her eyes.

- Nonverbal cues: She tapped her nails on the table. I braced for a question I didn’t want to answer.

Weak vs. Strong First-Person Dialogue Example

Weak:

“I don’t want to go,” I said.

“Why not?” she asked.

“Because I don’t feel like it,” I said.

“Fine. Stay here,” she said.

Strong:

“I don’t want to go,” I said, not meeting her eyes.

“Why not?” she asked, arms folded like a parent catching a lie.

“I just… don’t feel like it,” I shrugged.

“Fine. Stay here.” Her mouth tightened.

She didn’t slam the door, but she might as well have.

The second version shows emotion, body language, and subtext from the narrator’s perspective. This lets the reader experience the tension instead of simply reading about it.

How Can a First-Person Narrator Know About Events They Didn’t Witness?

One common question about first-person writing is: How do I show something the narrator didn’t see? Here are five ways to handle this while staying true to first-person limits:

- Dialogue: Another character tells the narrator what happened. “My mom told me he didn’t even cry at the funeral,” she said.

- Discovery: The narrator reads a letter, watches a video, or finds an object. I unfolded the note. Just six words: “I tried. You never saw me.”

- Rumors or Secondhand Info: Let the narrator hear it from someone else. Everyone said Mark was the last to see her. No one knew what they talked about.

- Dreams or Flashbacks (used carefully): These work when grounded in the narrator’s memory or subconscious. They should not be used as a lazy plot device.

- Imaginative speculation (with voice): The narrator may guess what happened, or misremember it entirely. This can lead to compelling, unreliable narration.

Final Thoughts

First-person writing is more than choosing a point of view. It’s choosing a relationship with the reader. When done right, it feels like confession, conversation, and story all at once.

It’s the voice that says:

“Let me tell you what really happened…”

Action to Experiment

Try rewriting a scene from your work-in-progress in first person. What does the character notice that a distant narrator wouldn’t? What do they leave out? How do they color the truth? Your character already has a story to tell. Let them tell it.

Do you have questions or comments? Ask Besty Bot about the writing craft and how to publish your book with Best Chance Media!

Copy and Share This Post on Your Social Media:

📚 Writers – Is First Person Right for Your Story?

“I opened the door and everything changed.”

That’s the power of first-person POV: raw, intimate, and immediate. But how do you show what your narrator didn’t see? How do you balance showing and telling?

🎯 This week’s post breaks it down:

- The show vs. tell sweet spot

- Writing real, revealing dialogue

- How to handle scenes the narrator missed

- Reviews of two standout first-person novels

✍️ Whether you’re revising or just starting out, first person might be the voice your story needs. AmWriting #WritingTips #FirstPersonPOV #ShowDontTell #WritersOfInstagram #WritingAdvice #FictionWriters #WritingCommunity #StorytellingTips #POVMatters #DialogueWriting https://bestchancemedia.org/2026/02/19/dialogue-in-first-person-showing-through-whats-said-and-left-unsaid/