A reflection on truth, memory, and the power of third-person omniscient narration

By Jennifer Braddock – Editor

Ever wanted to play god without the responsibility of smiting anyone? Welcome to third-person omniscient, where you know everything, see everything, and judge nothing. This is the narrative voice that floats above your characters. Before you put on your all-seeing narrator hat, let’s discuss the what, why, and how.

Third-Person Omniscient Traits and Boundaries

Why tell this story through the eyes of many? Because stories like the one about Camp Arroyo aren’t just about individuals. They’re about a system. A society. A truth that implicates everyone.

From this point of view, the narrator is not a character in the story. Instead, they’re an all-knowing presence who can dip into any character’s thoughts, emotions, memories, or future dreams, and offer commentary.

- You know everyone’s thoughts, but don’t share them all at once. Pick your spots. Otherwise, it’s emotional whiplash.

- The narrator has a tone. Even if it’s not a character, the voice telling the story has a personality: wry, wise, ironic, or lyrical.

- You can zoom in and out, but do so smoothly. Think of it like directing a movie: wide shots for scene-setting, close-ups for emotion.

- Avoid ‘head-hopping’ mid-paragraph. Just because you can see into every head doesn’t mean you should jump between them too fast.

I’ll illustrate these points using an example from a historical fiction book I’m writing, titled Vengeance at Stone Creek.

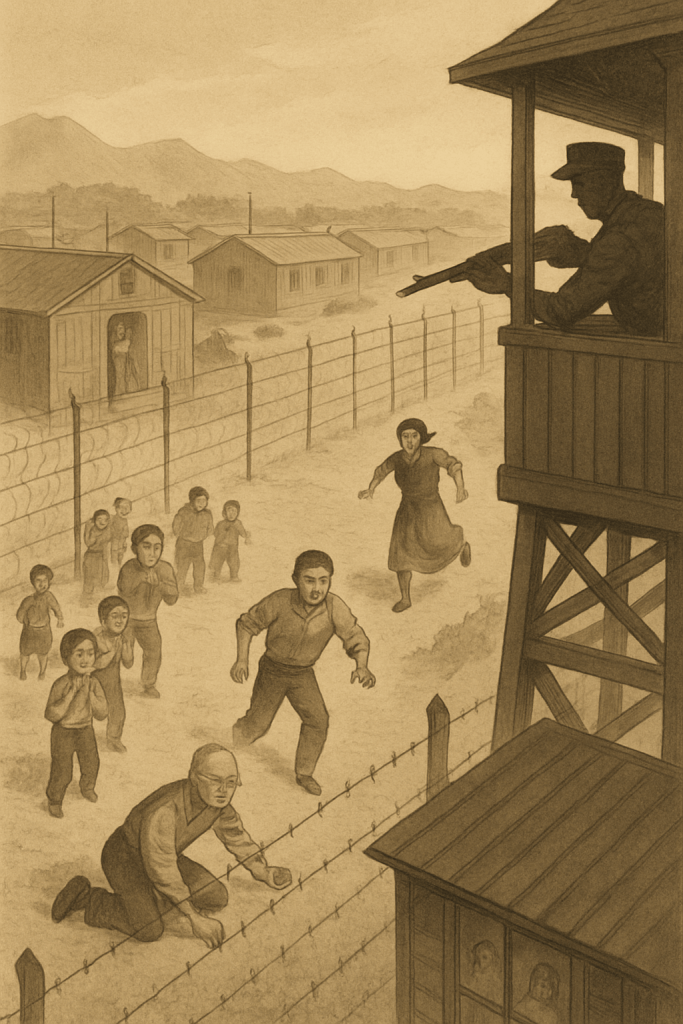

Camp Arroyo, Colorado, was one of ten wartime incarceration centers for Japanese Americans. It baked under the sun as it had every afternoon.

Children played. Mothers folded laundry. A sentry cleaned his rifle in the guard tower.

And then: the shots.

Tak Fujiyama was seven years old when he saw his friend Seito San collapse into the dust.

Everyone saw. No one stopped it. Sumiko, his mother, was already sprinting towards the commotion. The kitchen crew froze mid-prep, couldn’t scream. The guard, Pfc. Joe Darrow said nothing. He brushed the shell casings off the tower floor as if he were brushing crumbs from a table.

That moment changed everyone.

What About Dialogue?

In third-person omniscient, dialogue works the same way as other third-person perspectives:

“I’ll get you!” Tak screamed at Private Darrow, dusting the snow off his oversize Army coat. He hadn’t heard gunshots before and was shaken up by the whole ordeal

Darrow didn’t answer. He was wondering if he’d lose rank after the shooting incident.The narrator, meanwhile, knew what Tak and Darrow were thinking.

You can also add asides or commentary that no character would know, which gives the narrator that wise, slightly smug quality:

Sumiko was exhausted from running from the barracks. She wasn’t quite sure what had happened. She walked closer and was overwhelmed with what she saw.

The Show-Don’t-Tell Balance

Third-person omniscient gives you ultimate show/tell control. Want to show emotion? Zoom into a character’s thoughts. Want to tell us something about the world? Zoom out and narrate. Just make sure the shifts feel intentional, not chaotic.

This is the storyteller voice of classic literature (think Dickens or Tolstoy) and some modern epics. It’s panoramic, wise, and capable of zooming in or out at will.

Third-person omniscient narration gives readers access to collective memory. It allows us to hear not just what happens, but what’s felt. All at once, the story pulls back the curtain on silence, shame, complicity, and courage.

Tak’s disbelief lives beside Darrow’s detachment. Sumiko’s heartbreak collides with her son’s helplessness. Even the wind plays a role, carrying the sound across camp like a cruel messenger.

This perspective doesn’t dilute the pain, it amplifies it. When the reader knows what everyone knows, and still nothing stops the tragedy, the horror is total.

Truth Wrapped in Fiction

Tak’s story is fictional, but the bullets, the towers, and the silence are real. More than 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes during World War II. Most had committed no crime. Many were children, and some, like those at Camp Arroyo, never came home.

By using third-person omniscient narration, Vengeance at Stone Creek invites readers not to choose sides. Readers can see the whole landscape. They can sit in the shoes of the witness, the victim, the perpetrator, and the bystander.

Because when history repeats itself, it’s often because too many people looked away.

Your Role in the Story

You weren’t in the guard tower.

You weren’t holding the rifle.

You are here now, reading, remembering, deciding what comes next. The story isn’t just told from Tak’s point of view. That’s the point.

Third-person omniscient lets the reader see the entire moment. It reveals how trauma spreads across a scene like a shock wave. It goes from Seito San falling to Sumiko running and the cook dropping a spoon. It gives the reader access to the full spectrum of awareness, emotion, and silence.

First-person limits us to one set of eyes. Third-person limited creates a one mind boundary. Omniscient opens the sky.

It asks us not only to see, but to understand what was done, what was allowed, and what was ignored.

For Writers: A Call to Experiment

Are you a writer? Try writing a scene using third-person omniscient.

Let us feel not just the protagonist’s heart, but the room’s temperature.

Let us see the villain’s hesitation.

Let us watch a neighbor look away.

Give us the whole truth, not just a character’s version of it.

Third Person Omniscient isn’t just a Point of View. Its lens, conscience, and chorus. Use it wisely. Some stories don’t belong to one person.

They belong to all of us.

Do you have questions or comments? Ask Besty Bot about the writing craft and how to publish your book with Best Chance Media!

Copy and Share This Post on Your Social Media:

📚 Ever wished your story could show everything at once?

That’s the magic of third-person omniscient. You’re not just in one character’s head. You’re in everyone’s.

– The mother screaming.

– The soldier pretending not to care.

– The cook frozen mid-stir.

– The wind carrying truth through the Japanese internment camp.

In one shot, the whole world reacts, and you, the writer, see it all. 🖊️ Try it: Rewrite a key scene from your story using third-person omniscient.

– Feel the shift in power.

– See what your characters can’t hide.

#WritingTips #ThirdPersonOmniscient #NarrativeVoice #WritersOfInstagram #HistoricalFiction #PointOfView #WriteWithDepth #StorytellingCraft #FictionWriters #AmWriting https://bestchancemedia.org/2026/02/05/the-day-the-fence-took-everything/